Sections

Background

A late night on the vintage hardware side of eBay a few years ago netted me a Sony DXC-3000A broadcast video camera. I didn’t really have a plan for it, but I figured it could be fun to tinker with. And, as with all eBay deal rabbit-holes, I eventually ended up with a couple more cameras, lenses, accessories, service manuals, vectorscopes… all, of course, of varying quality. Some of the cameras (like the one in some of the pictures) ended up being the 3000 variant (without the A), which denotes that it’s not S-Video capable.

The Camera

Pinning down a release date for this camera is tough, but most of the components inside of it are datestamped 1986 or ‘87, and that seems to correlate with the first mentions I can find of it online. Like other professional equipment of the era, electrically it consists of a backplane with pluggable and serviceable modules, each with a different function, and each packed with TTL and analog components. The service manual is also readily available on archive.org which is extremely convenient. It contains the expected servicing instructions and block diagrams, but also complete schematics, PCB layouts, and BOMs.

The DXC-3000A is not a camcorder. As a piece of broadcast equipment, it’s designed to be used in a studio with a Camera Control Unit (CCU, with a big umbilical cord) or in the field with a portable Video Tape Recorder (VTR). To this end, it has a big socket with all of the camera control inputs and video outputs. It also has a BNC connector for genlock in, and another for composite video out. I think composite video gets somewhat of a bad rap among people who remember it in association with low-bandwidth videotape formats, but a well-driven high-bandwidth composite signal like this one produces looks remarkably good on a suitable display.

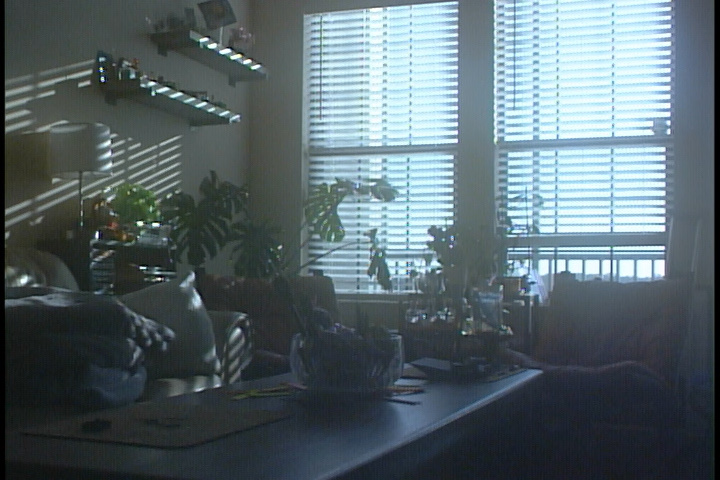

Well, like this one should produce. On this unit, the lens is nearly 40 years old, and the coatings are breaking down. I haven’t yet calibrated it, but I plan to: I’m sure even if it was calibrated when it was put into storage before I got it, the capacitors alone would have de-rated enough to need compensation in the last 30 or so years. As noted in the appendix, the camera is currently without an integrated IR-cut filter, so I’m using a lens-mounted filter instead. The image below is, of course, also routed through a cheap USB composite capture device. The room was dim, so the analog sensor gain was set to +9dB on the camera itself. Click the screenshot to watch the full video.

Something that the composite signal does a good job of hiding, however, is the fact that this camera has a discrete-pixel CCD sensor and not a continuously scanned video tube. In a way, the frontend is similar to that of a modern CCD/CMOS digital camera, as the pixels are read out sequentially, except here the charges for each pixel are processed entirely in the analog domain thereafter. This camera has 3 CCD sensors connected via a prism, giving red, green, and blue charges for each pixel without using a color filter.

EN-39

Among the modules connected to the backplane is one called the EN-39 (or EN-39A, for S-Video models). From the block diagram, it’s in charge of RGB buffering, YIQ matrix amplification, superimposing zebra stripes for the viewfinder, and composite/S-Video encoding. Basically, this module is entirely responsible for analog video output.

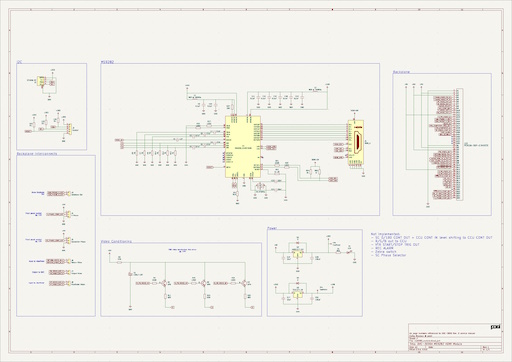

While reading through the service manual, this module in particular stood out: it takes in composite sync, and an instantaneous sample of analog RGB pixel data. If this sounds familiar, it’s almost electrically equivalent to VGA. The hitch is that the video is interlaced, the voltage range is incompatible (~1.5 Vpp with a ~3V DC bias, see the Waveforms appendix), and we don’t have separate H/V sync. I spent some time tinkering with the idea of a building a replacement module with an ADC, some sort of FPGA or microcontroller for interpreting the sync signal and timing, and HDMI output, but finding parts for the 3-channel 24-bit pipeline wasn’t cheap for spinning up test boards.

Wii2HDMI Misadventure

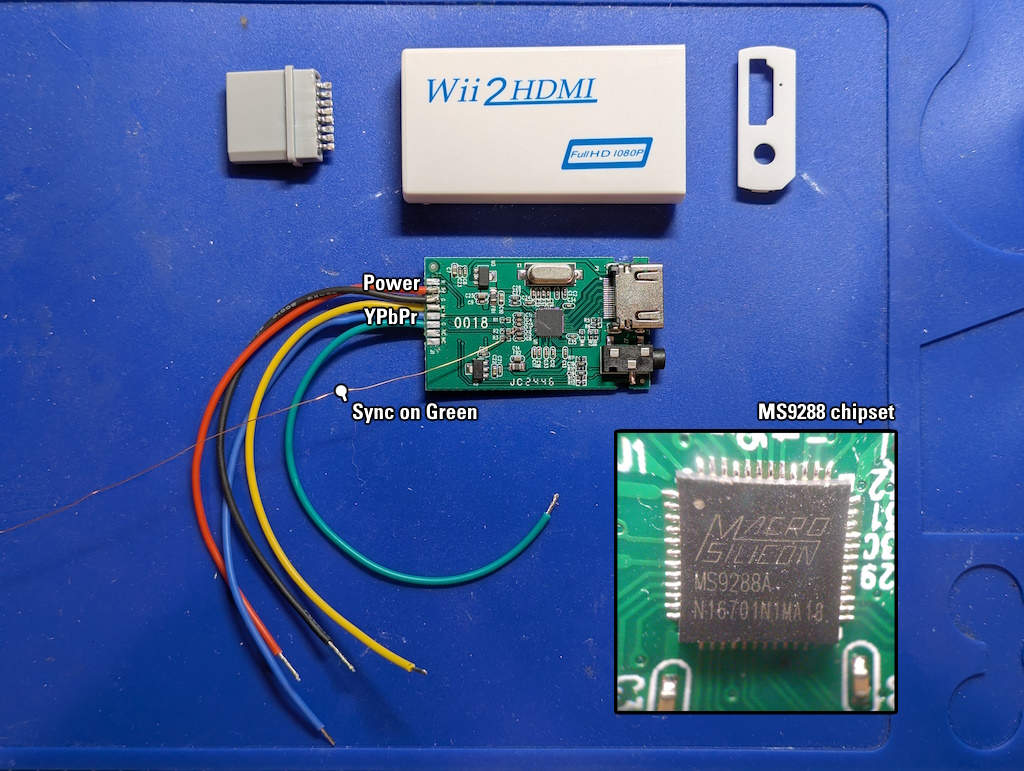

A while later, I came across an imported “Wii2HDMI” dongle, which converted the Wii’s component YPbPr output to HDMI. The converter board was extremely sparse, so I tracked down the chipset: a Macro Silicon MS9288A. In the one English datasheet I could find, it claimed to support RGB video and has a separate input for Sync on Green, which conveniently is a separate input to the EN-39 board (in the form of the aforementioned composite sync), but didn’t mention how it differentiated RGB video from YPbPr. Maybe it has some sort of heuristic on the input video? I didn’t see any jumpers mentioned in the datasheet. Hopeful, I replaced the Wii’s video connector with some jumper wire, removed the Sync on Green coupling capacitor, an tacked on an enameled magnet wire.

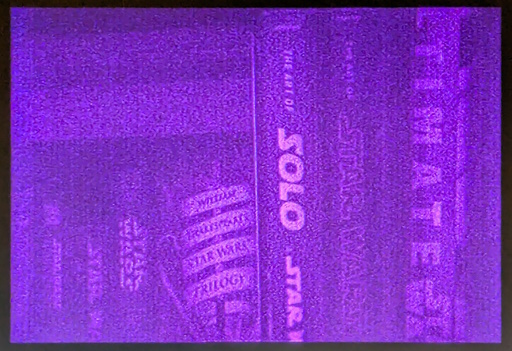

Connecting it to the inputs on the backplane yielded…

(Picture of a TV warning, apologies)

Hmm. Neither the scene nor the color bars I was hoping for. With my personal email, I spoke back and forth with someone at Macro Silicon, who was unfortunately tight-lipped about details and understandably unwilling to troubleshoot. Maybe it looks for the presence of H/V sync to deduce RGB (ostensibly VGA) video? I tried again through my business email and got better results: I was able to get a datasheet and an SDK for a related chip, the MS9282, which was supposedly higher quality but less self-contained, requiring I2C control. The kicker? It supported Sync on Green for RGB 480i video. It also was available at LCSC for cheap in small quantities. Dreams returned of replacing the analog encoder with a digital encoder… I was tentatively excited, so I had to know if it could work.

Analog to Digital Conversion

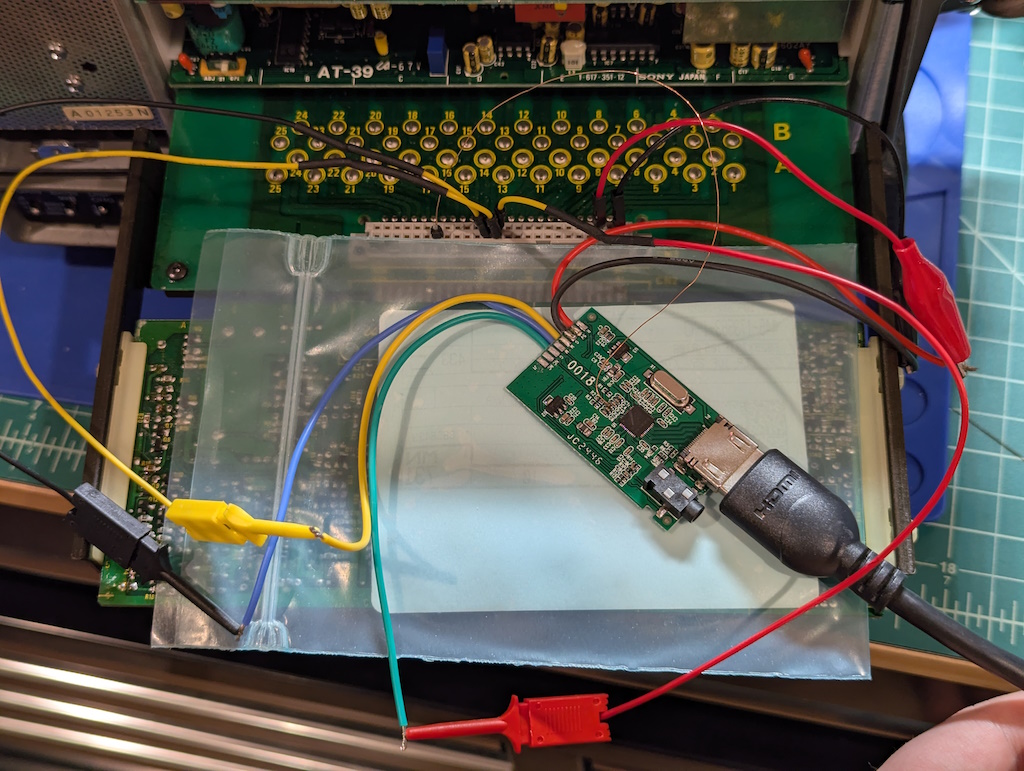

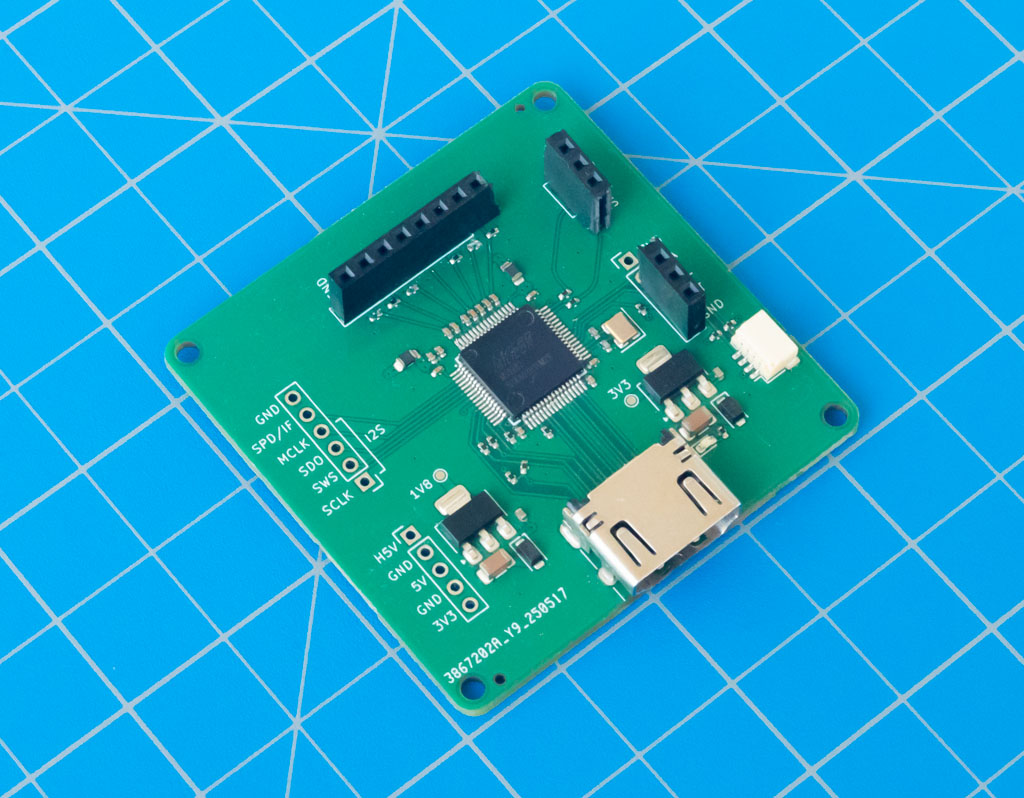

A few hours in KiCad (project linked below), a few weeks waiting for JLCPCB, and I had some MS9282 breakout boards. I spent some time implementing the HAL for their SDK to target the RP2040 and gave it a shot. All it took was connecting the RGB inputs to the same RGB bus as before from the EN-39’s backplane connector, and passing the backplane’s composite sync signal off as Sync on Green. For this test I didn’t even bother to buffer the RGB inputs, hoping that the signal levels would just work out after AC coupling.

Lucky guess! It looked like this might work out after all. I spun another board with the original driving components (the peculiar 2SC3326 transistor with termination resistors) and a breakout board with FPC connectors for the major backplane signals. It didn’t visually change the image quality (I suspect the input conditioning of the MS9282 is to thank), but it felt less creepy.

Feeling comfortable with that setup, I merged it all into a final design, this time with a spot for a Feather RP2040 and room for an HDMI cable with holes for cable-ties. Here it is, alongside the EN-39 board.

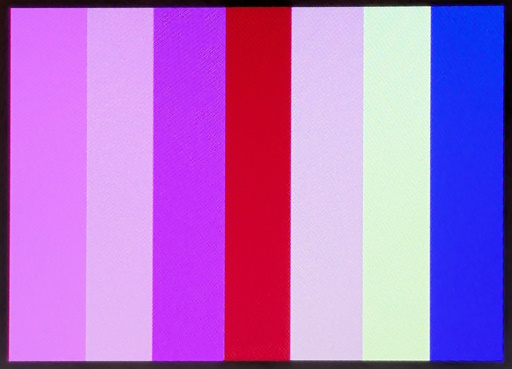

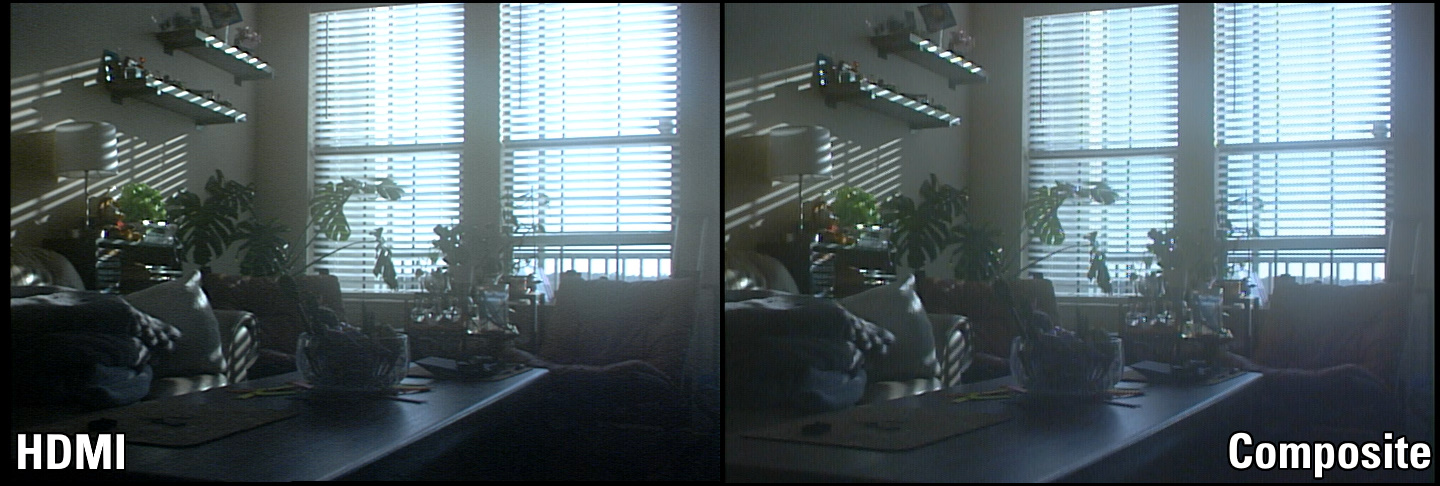

The MS9282 correctly sorts out the interlaced composite sync signal from the backplane and sorts the pixels into the right fields, which is great. For now I typically route the HDMI cable through the battery compartment. Finding a monitor or even TV around that supported the apparently oddball 480i resolution over HDMI was a challenge, and in the end I used a Blackmagic DeckLink Mini capture card, which didn’t list that format as supported in the manual, but seems to record it fine. The resulting video might not be broadcast-quality (or even “good”) by today’s standards but I think it’s a noticable improvement over composite or even S-Video for bright, noisy scenes. Click the screenshot to watch the full video.

You might have noticed that this screenshot looks remarkably similar to the composite-capture one. Indeed, they are the exact same frame of video! Sony made a backplane extension board (the EB-3000) to allow a module to operate outside the camera for servicing. It has multiple backplane connectors on it, and since the HDMI board is passive (with none of the expansion headers connected, as mentioned later), I connected it to one of the free headers alongside the EN-39 and recorded the output from both modules. Barring video capture and encoding quirks, the exact same RGB signals were encoded into the same frames from both modules, with the same camera settings.

Here is a comparison of the two screenshots, which are of the exact same frame of video:

And, for completeness, here is the same scene imaged with a modern DSLR, color corrected for “basically what I saw”:

Next Steps

The final board has a few extra headers that I haven’t mentioned previously: output video, viewfinder video, return video, subcarrier phase, horizontal phase, and earphone out. Naturally, the EN-39 was responsible for a little bit more than I initially understood. A big one is that it controls the video feed in the viewfinder, so to continue supporting those features, I added expansion headers to add more hardware later.

Where will that hardware live? Probably in the battery compartment: stay tuned for Part 2, where I discuss the Raspberry Pi-based HDMI capture setup that lives in the battery compartment, which is the next piece of the camcorder puzzle.

Appendix

KiCad files

Find the complete module on GitHub, under the CERN-OHL-P-2.0 license.

Connectors

- The CCU connector mates with a Hirose JRC16BP-14P(71).

- The lens connector mates with a Hirose HR10A-7P-6P(73).

- The backplane mates with a Hirose PCN10A-50P-2.54DS(72) (but any 50-position B-style DIN 41612 connector will do)

Spectrograms

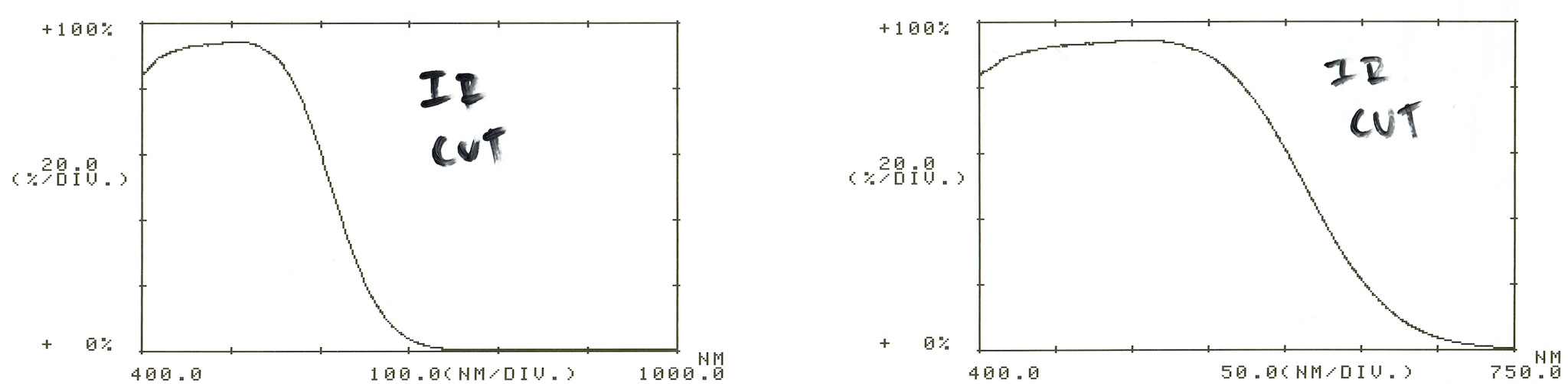

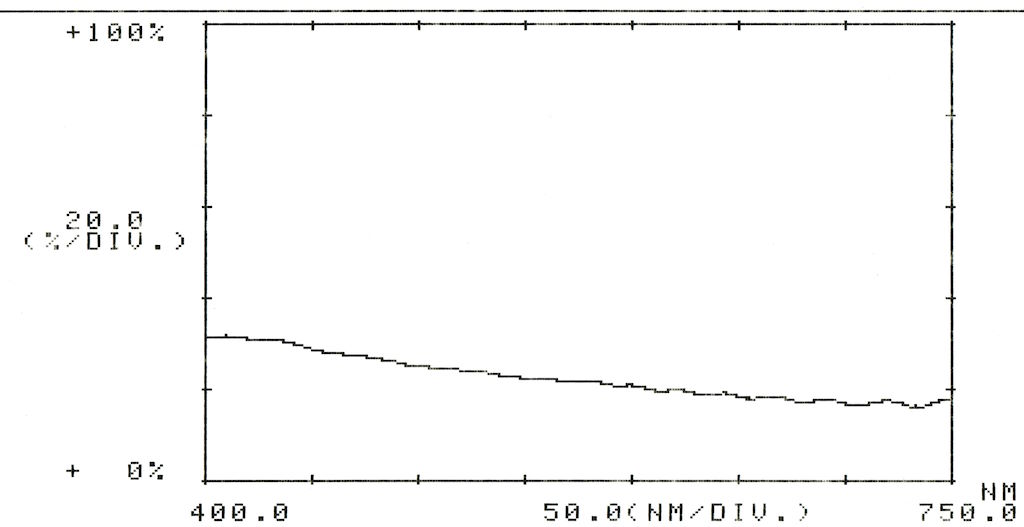

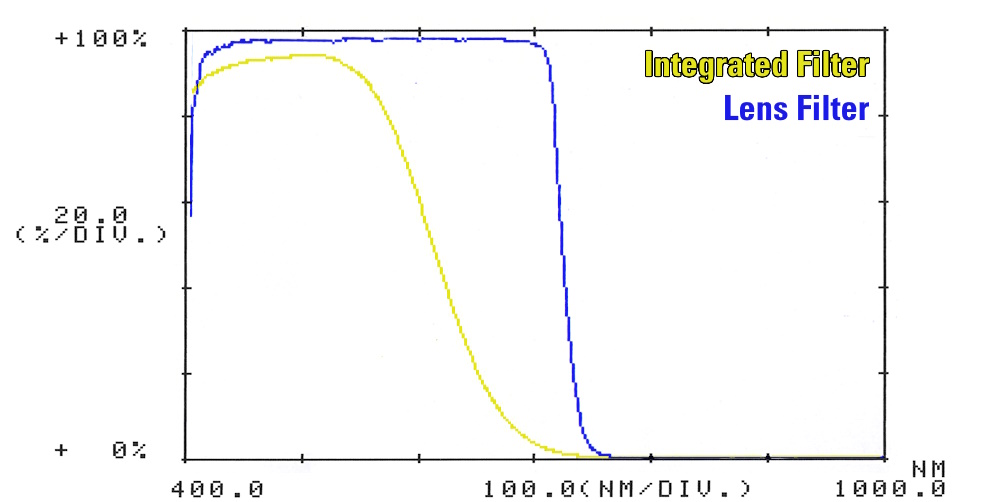

All filters were measured with a Shimadzu UV160U (hopefully the subject of a future post!), and the thermal printouts scanned.

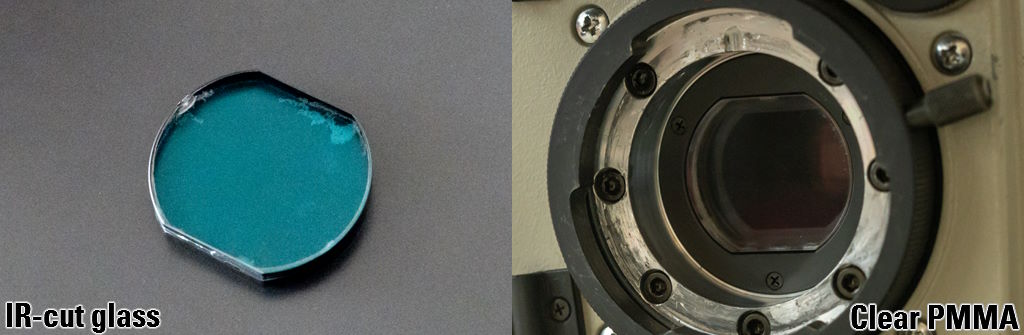

IR-cut filter

An infrared lowpass filter sits between the lens and the filter wheel. Unfortunately, the glass’ coating has significantly degraded, to the point of hazing the image, so I replaced it with piece of clear acrylic/PMMA cut to shape and vapor polished.

Here is the transmittance of the IR-cut filter:

I had some “low-E” window film lying around, and I was curious if I could apply some to the acrylic and have it behave somewhat more like the original filter. Unfortunately, the transmittance is more like an ND filter in the same part of the spectrum (shown below). I still like the idea of finding a film to apply, so maybe I can find one with similar characteristics.

In the meantime, I’m using an external lens-mounted filter, an “ICE Brand by Desmond Photographic” 77mm IR/UV filter. It compares better to the integrated filter, but it isn’t quite a perfect match:

Here is a quick, unscientific comparison between the two filters, superimposing their scans:

Filter wheel

A filter wheel sits between the IR-cut filter and the CCD, with three options:

-

3200K (effectively transparent)

-

5600K with a 1/8 ND filter

-

5600K

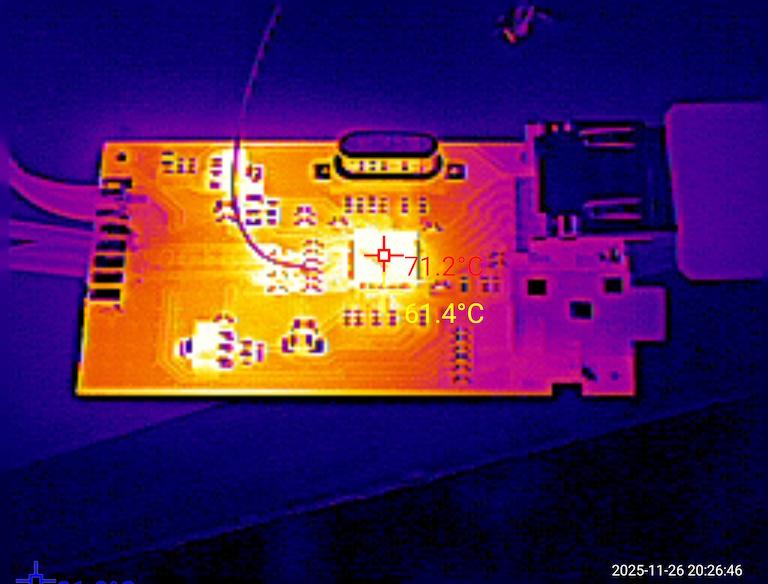

Thermograms

I took a thermogram of the Wii2HDMI board while it was operating alongside the EN-39, and the chipset was pushing 70°C. Might be something to keep in mind if you’re using it for the intended purpose, since the enclosure isn’t ventilated at all.

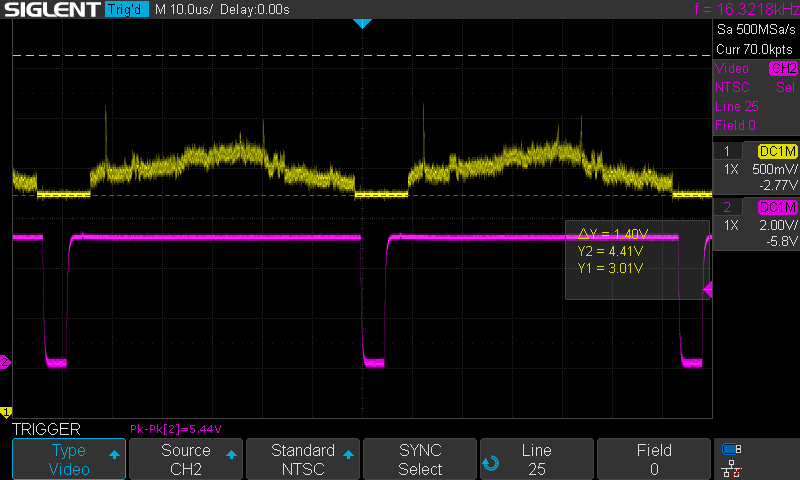

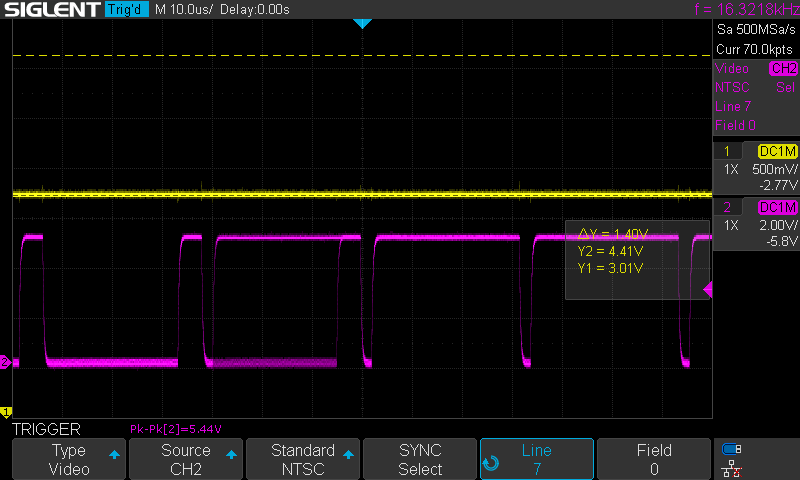

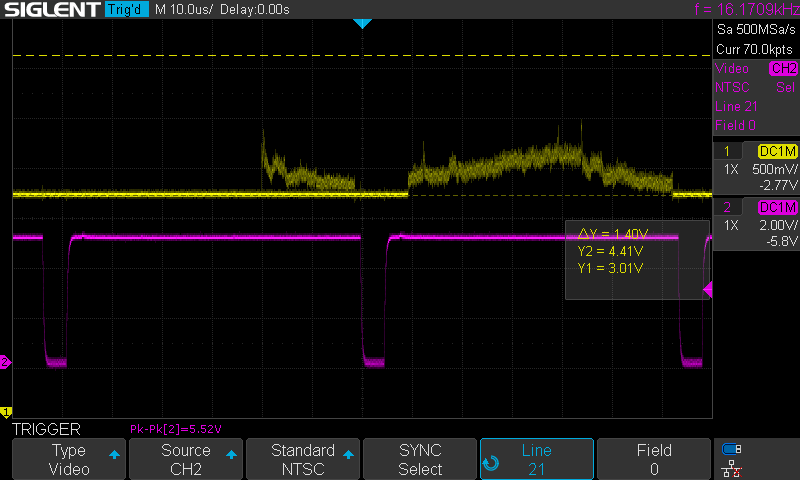

Waveforms

Here are 3 waveforms, all captured with a Siglent SDS1104X-E. Channel 1 (yellow, top) shows one of the RGB channels coming from the backplane (~1.5 Vpp, ~3V DC offset), and channel 2 (magenta, bottom) shows the composite sync TTL signal (5 Vpp).

-

Triggered on NTSC line 7

-

Triggered on NTSC line 21

-

Triggered on NTSC line 25